This post is the part one of a series on writing a SVG parser in Go. It is inspired by the amazing book from Thorsten Ball (https://interpreterbook.com/).

As developers, we use parsers everyday: from web browser engines, to compilers, interpreters and linters.

But when it comes to write one yourself, for instance to read a custom config file, or protocol, where would you start?

Most of the time the easiest way is to generate the code of the parser using a generator, like yacc or ANTLR. Let’s see how to build one ourselves.

In this series I decided to render SVG to PNG.

SVG is easy to parse: it has a simple XML syntax. And seeing the result of your parsing as an image is fun and motivating.

Let’s go!

What’s in our parser?

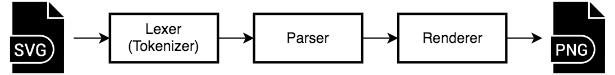

There are different types of parsers. Here we’re going to write the combination of a lexer (tokenizer) and a parser.

The lexer will read the input SVG file, and produce a list of tokens.

The parser will take these tokens as input, and produce a structure representing the content of the SVG file.

This structure can be a tree, or some kind of hierarchy.

Note:

This article is here to teach you about lexing and parsing. For this purpose, we will not properly build a XML DOM tree. We will discuss it later.

As a last step, we will read this structure to paint to a PNG.

This can be summarized with the following chart.

The tokens

The first step is to define the set of tokens our lexer is going to output.

A token can be a symbol or a string of symbols.

What tokens do we need for our lexer? To answer this question, let’s look at an example SVG file:

<svg width="100" height="100">

<circle cx="15" cy="0" r="50" stroke="00FF00" stroke-width="4" fill="FFFF00" />

<circle cx="90" cy="80" r="40" stroke="F00" stroke-width="2" fill="00F" />

</svg>

Note:

For simplicity I use hex colors without the leading hash sign

#.

So we’ve got the following tokens:

- Opening bracket:

< - Tag names:

svg,circle, … - Closing bracket:

> - Slash:

/ - Equal sign:

= - Double quotes:

" - Attributes names:

height,stroke-width, … - Attributes values: strings and numbers

Given that our lexer has to return a list of tokens (most likely a slice in Go), we can go ahead and create a Token type.

We notice there are two types of tokens: key characters and literals. We can make everything simple by attributing a type and a litteral to each token.

Note that I am adding End Of File (EOF) and an Illegal token types. They will be used later to indicate respectively the end of our input file, or a tokenizer error.

type TokenType string

const (

EOF TokenType = "EOF"

ILLEGAL TokenType = "ILLEGAL"

TokenOpen TokenType = "<"

TokenClose TokenType = ">"

TokenSlash TokenType = "/"

TokenQuote TokenType = "\""

TokenEqual TokenType = "="

TokenIdentifier TokenType = "IDENT"

)

type Token struct {

Type TokenType

Literal string

}

If this does not make much sense yet, don’t worry, it will when we get to write our first test.

The lexer

Let’s jump into the fun part: writing the lexer. I will write unit tests along the way. Our lexer will not give an interesting output so tests are the best way to quickly check it works as expected.

What will the lexer look like?

type Lexer struct {

input string

currentPosition int

nextPosition int

ch byte

}

Nothing surprising here, excepted maybe the nextPosition field. Our lexer will need the ability to see one character ahead, to know the type of the token being read. More on this when we will read TokenIdentifiers.

Note:

For simplicity the lexer will work with string rather than io.Writer, and it will read this string byte by byte. It means we might get into trouble to correctly read Unicode input files.

Before writing our first test, let’s define the main method of our lexer, to get the list of all tokens.

The first idea would be to write something like:

func (l *Lexer) GetAllTokens() []Token

While this could work in most cases, imagine the memory cost parsing an enormous input file. It would create a huge slice of Tokens.

To fix this issue, we can use an iterative lexer instead, whose main method would iterate each token successively.

func (l *Lexer) NextToken() Token {

// ...

}

It would simply return a token with Type EOF when it’s read all the input file. Way more efficient!

If it was not clear before, you should see the interest of the EOF TokenType now, as well as the fact we use currentPosition and nextPosition, so our lexer knows exactly where it is inside the input string.

Some tests for our lexer

We need to test the NextToken() method. The following test should be easy to understand if you are familiar with Go testing package.

Note that I chose a meaningless input. The lexer is not interested into understanding SVG, but rather into recognizing SVG tokens, which it will do fine with the following input.

Also note the whitespaces in the input, between tokens, not inside an identifier, as it would break it into two.

func TestNextToken(t *testing.T) {

input := `/> ab-cd< "= *123`

expectedTokens := []Token{

{TokenSlash, "/"},

{TokenClose, ">"},

{TokenIdentifier, "ab-cd"},

{TokenOpen, "<"},

{TokenQuote, "\""},

{TokenEqual, "="},

{ILLEGAL, "*"},

{TokenIdentifier, "123"},

{EOF, ""},

}

l := NewLexer(input)

for i, expected := range expectedTokens {

tok := l.NextToken()

if tok.Type != expected.Type {

t.Fatalf("wrong token[%d]. Expected type=%q, got=%q", i, expected.Type, tok.Type)

}

if tok.Literal != expected.Literal {

t.Fatalf("wrong token[%d]. Expected literal=%q, got=%q", i, expected.Literal, tok.Literal)

}

}

}

This is not compiling yet, as we’re missing the NewLexer function, which will be used to initialize the lexer, and set it ready to tokenize its input.

After initialization, we want the lexer to have currentPosition = 0 and nextPosition = 1.

To do so, our lexer will need two utility methods: peekChar to return the next character in the input string, but without changing our lexer state.

And readChar to update the lexer state and make it point to the next character (held by the ch field of our lexer).

func NewLexer(input string) *Lexer {

lexer := Lexer{input: input}

lexer.readChar()

return &lexer

}

func (l *Lexer) readChar() {

l.ch = l.peekChar()

l.currentPosition = l.nextPosition

l.nextPosition++

}

func (l *Lexer) peekChar() byte {

if l.nextPosition >= len(l.input) {

return 0

}

return l.input[l.nextPosition]

}

We make sure to check that nextPosition is within the input bounds, otherwise we return 0 (null char).

Our code should now compile, and our test fail. Let’s fix it now.

A working lexer

Let’s start with the skeleton of our NextToken method.

A switch statement, an making sure we advance by calling readChar should be all we need.

Or is it? We would be able to read some of our tokens, but something is missing. Our lexer needs to be able to comsume whitespaces, and ignore them to go the next non-whitespace character.

func (l *Lexer) readWhitespace() {

for isWhitespace(l.ch) {

l.readChar()

}

}

func isWhitespace(char byte) bool {

return char == ' ' || char == '\t' || char == '\n' || char == '\r'

}

Notes:

As said earlier, we handle bytes only, but this isWhitespace method can be extended to handle Unicode. And Go has everything in its standard library:

unicode.IsSpace(r rune) bool(https://golang.org/pkg/unicode/)Notice the

readWhitespacename, starting byread. I will use it as a convention for methods updating the state of the parser.

This leaves us with the following code.

func (l *Lexer) NextToken() Token {

var tok Token

l.readWhitespace()

switch l.ch {

case '<':

tok = Token{TokenOpen, string(l.ch)}

case '>':

tok = Token{TokenClose, string(l.ch)}

case '/':

tok = Token{TokenSlash, string(l.ch)}

case '"':

tok = Token{TokenQuote, string(l.ch)}

case '=':

tok = Token{TokenEqual, string(l.ch)}

case 0:

tok.Type = EOF

default:

tok = Token{ILLEGAL, string(l.ch)}

l.readChar()

return tok

}

With this version, we can almost make our test pass. By the way, if a test almost passing means something for you, I suggest you reconsider the concept of test.

Joke apart, with this input, our test passes! Yes!

input := `/> < "= *`

expectedTokens := []Token{

{TokenSlash, "/"},

{TokenClose, ">"},

{TokenOpen, "<"},

{TokenQuote, "\""},

{TokenEqual, "="},

{ILLEGAL, "*"},

{EOF, ""},

}

Handling identifier tokens

We’re almost done with our lexer. We need to add the ability to parse identifiers, strings or numbers like:

circlestroke-width1234

This will not be handled with a simple switch case, but rather in the default case. We need a way to identify a character belonging to an identifier. In our case it will be all alphanumeric characters, lower and upper-case, and the dash -.

In the way we wrote isWhitespace, we can write isAlphaNumDash.

func isAlphaNumDash(char byte) bool {

return isLetter(char) || isDigit(char) || char == '-'

}

func isLetter(char byte) bool {

return 'a' <= char && char <= 'z' || 'A' <= char && char <= 'Z'

}

func isDigit(char byte) bool {

return '0' <= char && char <= '9'

}

Note:

Here again

unicodepackage has the appropriate methods to work with Unicode points.

Let’s come back to our default case:

default:

if isAlphaNumDash(l.ch) {

tok.Literal = l.readIdentifier()

tok.Type = TokenIdentifier

return tok

} else {

tok = Token{ILLEGAL, string(l.ch)}

}

We now need to write the readIdentifier method. It is prefixed by read, which means it will comsume characters and update our lexer state.

So we need to make sure we don’t call l.readChar() after reading an identifier. This is why we return the token right away.

No more suspense, here is our method. We need to make sure we keep the start position, to return a sub slice of the lexer’s input.

func (l *Lexer) readIdentifier() string {

startPos := l.currentPosition

for isAlphaNumDash(l.ch) {

l.readChar()

}

return l.input[startPos:l.currentPosition]

}

If we go back to the full version of our test, it should now be passing. How good is that?

Before going on

I think this lexer architecture is brilliant, and very flexible. All credit goes to Thorsten Ball and his amazing book: https://interpreterbook.com/.

I’ve seen several parser implementations in Go using the same structure, and so should you if you have to create your own lexer.

It is easy to improve, easy to test and I think, easy to read.

I will see you in the next post of this series, to write the actual parser and tackle SVG rendering.